A recent study found that individuals with autism spectrum condition (ASC) demonstrate a tradeoff between speed and accuracy when faced with emotionally-charged situations with conflict. It is well established that individuals with ASC tend to pay less attention to social and emotional information, so one possible explanation for this finding is that individuals with ASC incorporate less of that information into their decision-making than neurotypicals, allowing them to make decisions faster without it. However, ignoring social cues can result in incorrect responses if the task or decision requires correctly interpreting others’ emotions. Sometimes quick, non-social decision making can be beneficial, but in other situations it could have undesirable consequences.

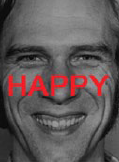

Whitney Worsham of Brigham Young University and colleagues asked 32 teens with autism and 27 without to press a key to identify the emotion (either fear or happiness) on an image of a complete face. The experimenters introduced conflict by overlaying a word on the face. Sometimes the word matched the facial emotion (“happy” on a happy face), and sometimes it didn’t (“fear” on a happy face). The experiment included both male and female faces, and the order of matching and non-matching images was random. The participants each completed 450 experimental trials: they clicked “fear” or “happy” for 450 faces, in three blocks of 150, with untimed breaks between blocks.

Overall, both ASC and control participants responded more slowly to non-matching word-face combinations than to matching ones. Both groups also demonstrated the same degree of “conflict adaptation.” Participants were slower to respond during trials that followed a matching trial than ones that followed a non-matching trial. Individuals subconsciously recruit more cognitive resources for the more difficult task of identifying the facial emotion with an opposite overlaid word—that’s the adaptation to conflict. Then, those extra resources result in a quicker response on the next trial, regardless of whether it matches or not. The insignificant difference between ASC and neurotypical participants in this area suggests that cognitive adaptation is intact, at least measured by behavioral responses. Importantly, the ASC participants had quicker response times overall, and the difference was much greater for non-matching trials.

Overall, both ASC and controls were more accurate on matching trials, with minimal differences between groups. However, the ASC participants were significantly less accurate on non-matching trials. Interestingly, there was a correlation between speed and accuracy for the ASC participants only on the non-matching trials. The longer a person with ASC took to respond to the non-matching trials, the greater their accuracy was on both non-matching and matching trials. There was no correlation between speed and accuracy on either type of trial in the neurotypical participants. The authors noted that they had not seen the correlation observed in the ASC group in a previous study that used a completely non-emotional task.

The authors suggested possible reasons for the less-accurate results in the ASC group. According to Just et al. (2004, TRANSLATE 10/14/2015), individual brain regions may be fully intact, but they may have a harder time working together in individuals with ASC. That means that tasks requiring integration of several brain regions, such as interpreting social situations, are more challenging for people on the autism spectrum. Worsham et al.’s experiment asked participants to mentally juggle words and images, and it also included a social component. She recommended repeating the study design with even more complex stimuli, such as videos of people acting out the emotions, to test whether the discrepancy between ASC and neurotypical participants would widen.

Also, the ASC group might have responded more quickly because they paid less attention to the social part of the stimulus. It has been shown that individuals with autism do not draw as much information from facial expressions as their neurotypical peers, and some find making eye contact uncomfortable or threatening. Their decisions may have been based mostly on the overlaid text, resulting in fast but inaccurate decisions during the trials with conflict.

This study suggests that individuals with ASC carry out conflict adaptation to the same level as their neurotypical peers. The work also suggests that those with ASC tend to make decisions more quickly in emotionally-charged situations that contain conflict, which may not be ideal in some situations. Mindfulness training (TRANSLATE 12/4/2015) and training to help individuals on the autism spectrum interact with police safely (TRANSLATE 10/14/2015) are two examples of interventions that can help.

This research did not examine brain activity during the task, but the authors encouraged it for future work. That data would go beyond the behavioral response to help explain how individuals with autism process emotional situations with conflict.

The original article is available here:

Worsham W, Gray W, Larson M, South M. (2014). Conflict adaptation and congruency sequence effects to social-emotional stimuli in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19(8):897-905.